The Drugged Driving Problem

Impairing Effects of Drugs

There are many drugs – including illegal, prescription and over-the-counter drugs – that have impairing effects. Drug use can negatively impact coordination, reaction time, tracking, judgement, attention, and perception. The impairing effects of drugs may vary from person to person based on tolerance as well as drug-to-drug and drug-to-alcohol interactions. Impairment can be long-lasting.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) developed Drugs and Human Performance Fact Sheets reviewing the pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, duration of effects, drug interactions and performance effects for the following impairing drugs:

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)

Methadone

Methamphetamine (and Amphetamine)

Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy)

Morphine (and Heroin)

Phencyclidine (PCP)

Toluene

Zolpidem (and Zaleplon, Zopiclone)

Cannabis/Marijuana

Carisoprodol (and Meprobamate)

Cocaine

Dextromethorphan

Diazepam

Diphenhydramine

Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate (GHB, GBL, and 1,4-BD)

Ketamine

The National Institute on Drug Abuse also provides fact sheets on the short- and long-term health effects of varying illegal drugs.

Many scientific research studies have examined effects of specific drugs on driving among drug users, with particular interest in marijuana (see e.g., Hartman & Huestis, 2013, Cannabis effects on driving skills) and the combination of marijuana and alcohol (see e.g., Li, Chihuri & Brady, 2017, Role of alcohol and marijuana use in the initiation of fatal two-vehicle crashes; Chihuri, Li & Chen, 2017, Interaction of marijuana and alcohol on fatal motor vehicle crash risk: a case-control study).

Rates of Drugged Driving

There is a substantial body of drugged driving research that clearly shows the high rates of drugs among drivers on the nation’s roads. From self-report data we know that in 2019, 28.7 million Americans aged 16 and older drove under the influence: 13.6 million Americans drove under the influence of illicit drugs and 12.8 million specifically drove under the influence of marijuana. Drugged driving was most prevalent among young drivers, aged 21-25 (12.7%) and aged 16-20 (9.4%).

In 2007 the National Roadside Survey (NRS) conducted by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) first included drug testing in addition to alcohol, showing 16.3% of weekend nighttime drivers were positive for potentially impairing drugs.

The most recent NRS conducted in 2013-2014 reported that about 22% of drivers were positive for a potentially impairing drug during both weekday days and weekend nights. Notably, 12% and 15% of these groups, respectively, were specifically positive for illegal drugs including marijuana. Among weekday day drivers, 1.1% were alcohol-positive and 8.3% of weekend night drivers were alcohol-positive.

The table at left from the Governors Highway Safety Association and Foundation for Advancing Alcohol Responsibility assembles 2013-14 NRS findings for various substances among drivers during weekday days and weekend nights.

A 2018 study of young adults age 18-25 seeking care in an emergency department were surveyed about past-year substance use behaviors including drugged driving. Nearly one quarter — 24% — reported driving impaired by drugs in the past year, with 96% reporting driving after marijuana use. 25% of drugged drivers reported engaging in high-frequency drugged driving, 10 or more times in the past year.

Drug-Related Crashes, Injuries and Deaths

The extent of the drugged driving problem in the United States is only partially understood. In part this is due to limits on drug tests that are conducted on impaired driving suspects, drivers injured in motor vehicle crashes and fatally injured drivers. However, the available data on these drivers and crash victims presents a compelling picture about the negative impact of drugged driving on public safety.

The Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) is a national census of data on fatal injuries suffered in motor vehicle crashes. A 2018 report from the Governors Highway Safety Association showed in 2016 43.6% of drivers in FARS with known drug test results were drug-positive. Over half of drug-positive drivers were positive for two or more drugs and 40.7% of drug-positive drivers were also positive for alcohol. Marijuana was the most common drug among fatally-injured drivers -- its prevalence has increased in recent years as well as the prevalence of opioids.

The prevalence of drugs among deceased drivers has increased from 33% drug-positive in 2009 to 43% drug-positive in 2015. The imperative need to improve FARS data collection and reporting is discussed under Areas for More Research.

As shown below left, European crash risk studies have shown that drugs increase relative risk of crash for specific drugs; however, it is essential to remember that the limitless combinations of individual drugs and alcohol make determining crash risk more complex.

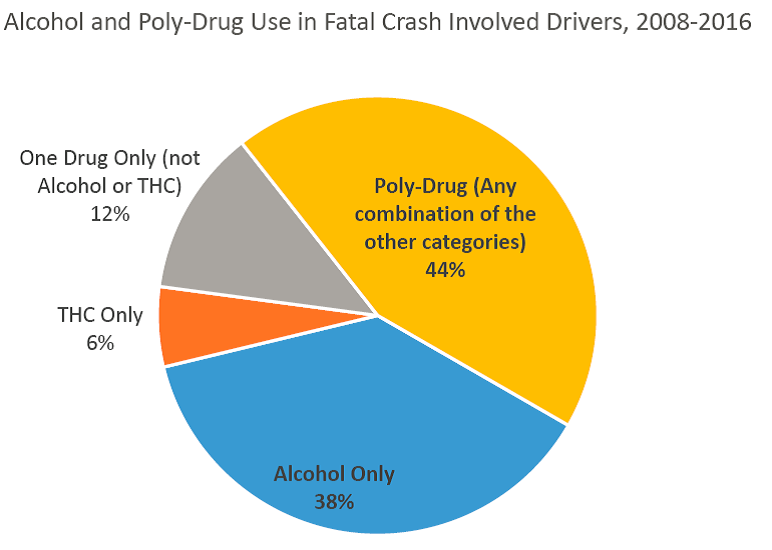

A 2005 study of seriously injured drivers showed over two thirds tested positive for alcohol and/or drugs, and 25% tested positive for more than one substance. The breakdown of drivers (shown above right) demonstrates common occurrence of polysubstance use.

A Focus on Marijuana

The Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (RM-HIDTA) tracks the consequences of commercial recreational marijuana in the state of Colorado, including the prevalence of marijuana-related drugged driving. Among its findings:

Since recreational marijuana was legalized in 2013, traffic deaths in which drivers tested positive for marijuana increased 135% while all Colorado traffic deaths increased 24%…This equates to one person killed every 3 1/2 days in 2019 compared to one person killed every 6 1/2 days in 2013.

The AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety showed that fatal crashes involving marijuana doubled after marijuana was legalized and commercialized in Washington State.

Some of the highlights of a the Washington Traffic Safety Commission released in April 2018 include:

Nearly one in five daytime drivers may be under the influence of marijuana, up from less than one in 10 drivers prior to the implementation of marijuana retail sales.

Poly-drug drivers is now the most common type of impairment among drivers in fatal crashes.

Alcohol and THC combined is the most common poly-drug combination.

39.1 percent of drivers who have used marijuana in the previous year admit to driving within three hours of marijuana use.

More than half (53 percent) of drivers ages 15-20 believe marijuana use made their driving better.

Among drivers positive for THC in Colorado in 2019 (shown at left), only 33% were positive for marijuana only; 35% were positive for marijuana and alcohol, 16% positive for marijuana and other drugs and 16% positive for marijuana, alcohol and other drugs.

Read a Viewpoint published in the Journal of the American Medical Association , "Driving Under the Influence of Cannabis: An Increasing Public Health Concern."

The Impact of COVID-19

During the early months of the pandemic, driving patterns changed. Although people made fewer trips , drivers engaged in riskier behaviors, including driving under the influence of drugs. The result is that while the total number of crash fatalities declined, the fatally rate increased.

A 2019-2020 NHTSA-funded study found a significant increase in the prevalence of drugs detected in blood among seriously and fatally injured drivers, from 50.8% before the pandemic to 64.7% and 61.4%, during the two pandemic periods.

More drivers tested positive for active THC than alcohol during the pandemic in Study Period 1.

The proportion of drivers that tested positive for opioids nearly doubled from before the pandemic (7.5%) to during the pandemic in Study Period 1 (13.9%) and Study Period 2 (13.4%).

The proportion of drivers that tested positive for two or more categories of drugs increased from 17.6% before the pandemic to 25.3% during the pandemic in Study Period 1 and 24.7% in Study Period 2.

Need for Public Education

The impairing effects of drugs are greatly underappreciated by the public. The mantra “Don’t Drink and Drive” is widely accepted – we need to add the message “Don’t Drug and Drive.” The Government Accountability Office has underscored the need for education and in particular strong federal leadership it its report Drug-Impaired Driving: Additional Support Needed for Public Awareness Initiatives.

In 2018 the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) launched a new campaign If You Feel Different, You Drive Different.

In light of state-based marijuana legalization, the need for education on the impairing effects of marijuana (alone and in combination of with other drugs) is even more pressing. The report Drug-Impaired Driving: A Guide for States from the Governors Highway Safety Association and Foundation for Advancing Alcohol Responsibility noted the following disturbing perceptions among marijuana users in states with commercial legal marijuana:

In surveys and focus groups with regular marijuana users in Colorado and Washington, almost all believed that marijuana doesn’t impair their driving, and some believed that marijuana improves their driving (CDOT, 2014; PIRE, 2014; Hartman and Huestis, 2013). Most regular marijuana users surveyed in Colorado and Washington drove “high” on a regular basis. They believed it is safer to drive after using marijuana than after drinking alcohol. They believed that they have developed a tolerance for marijuana effects and can compensate for any effects, for instance by driving more slowly or by allowing greater headways. However, Ramaekers et al. (2016) found that marijuana effects on cognitive performance were similar for both frequent and infrequent marijuana users.

The Colorado Department of Transportation has released numerous public service announcements on marijuana-impaired driving:

Other nations including Australia and New Zealand which have enforced strong laws against drugged driving have issued their own public education campaigns:

Recommended Reading + Resources

The following is not a comprehensive list of related reading and resources but serves as a starting point for more information on these drugged driving issues. Be sure to also check out the Resources page.

Drugged Driving Surveys

Berning, A., Compton, R., and Wochinger, K. (2015). Results of the 2013–2014 National Roadside Survey of Alcohol and Drug Use by Drivers. Traffic Safety Facts Research Note. DOT HS 812 118. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

2013-2014 National Roadside Survey on Alcohol and Drug Use by Drivers

2007 National Roadside Survey on Alcohol and Drug Use by Drivers

Bonar, E. E., et al. (2018). Prevalence and motives for drugged driving among emerging adults presenting to an emergency department. Addictive Behaviors, 78, 80-84.

Drug-involved Crash, Injury + Death

Bédard, M., Dubois, S., & Weaver, B. (2007). The impact of cannabis on driving. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 98(1), 6-11.

Biecheler, M. B., Peytavin, J. F., Facy, F., & Martineau, H. (2008). SAM survey on “drugs and fatal accidents”: search of substances consumed and comparison between drivers involved under the influence of alcohol or cannabis. Traffic Injury Prevention, 9(1),1-21.

Chihuri, S., Li, G., & Chen, Q. (2017). Interaction of marijuana and alcohol on fatal motor vehicle crash risk: a case-control study. Injury Epidemiology, 4(1), 8.

Drummer, O. H., et al. (2004). The involvement of drugs in drivers of motor vehicles killed in Australian road traffic crashes. Accident; Analysis and Prevention, 36(2), 239-248.

Governors Highway Safety Association and Foundation for Advancing Alcohol Responsibility. (2018). Drug-Impaired Driving: Marijuana and Opioids Raise Critical Issues for States. Washington, DC: GHSA.

Hedlund, J. (2015). Drug-Impaired Driving: A Guide for What States Can Do. Washington, DC: Governors Highway Safety Association.

Li, G., Chihuri, S., & Brady, J. E. (2017).Role of alcohol and marijuana use in the initiation of fatal two-vehicle crashes. Annals of Epidemiology, 27(5), 342-347.

National Center for Statistics and Analysis. (2020, October). Early estimate of motor vehicle traffic fatalities for the first half (Jan–Jun) of 2020 (Crash Stats Brief Statistical Summary. Report No. DOT HS 813 004). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Office of Behavioral Safety Research. (2021, January). Update to special reports on traffic safety During the COVID-19 public health emergency: Third quarter data. (Report No. DOT HS 813 069). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Tefft, B. C., Arnold, L. S., & Grabowski, J. C. (2016). Prevalence of Marijuana Involvement in Fatal Crashes: Washington, 2010-2014. Washington, DC: AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety.

Thomas, F. D., Berning, A., Darrah, J., Graham, L., Blomberg, R., Griggs, C., Crandall, M., Schulman, C., Kozar, R., Neavyn, M., Cunningham, K., Ehsani, J., Fell, J., Whitehill, J., Babu, K., Lai, J., and Rayner, M. (2020, October). Drug and alcohol prevalence in seriously and fatally injured road users before and during the COVID-19 public health emergency. (Report No. DOT HS 813 018). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Walsh, J. M., Flegel, R., Atkins, R., Cangianelli, L. A., Cooper, C., Welsh, C., & Kerns, T. J. (2005). Drug and alcohol use among drivers admitted to a Level-1 trauma center. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 37(5), 894–901.

Washington Traffic Safety Commission (WTSC). (2016). Driver Toxicology Testing and the Involvement of Marijuana in Fatal Crashes, 2010-2014. Olympia, WA: WTSC.

Marijuana-Impaired Driving

Asbridge, M., J. A. Hayden, and J. L. Cartwright. 2012. Acute cannabis consumption and motor vehicle collision risk: Systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis. BMJ 344:e536.

Desrosiers, N. A., Ramaekers, J. G., Chauchard, E., Gorelick, D. A., & Huestis, M. A. (2015). Smoked cannabis’ psychomotor and neurocognitive effects in occasional and frequent smokers. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 39(4), 251-261.

Downey, L. A., et al. (2013). The effects of cannabis and alcohol on simulated driving: Influences of dose and experience. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 50, 879-886.

Hartman, R. L., & Huestis, M. A. (2013). Cannabis effects on driving skills. Clinical Chemistry, 59(3), 478-492.

Hartman, R. L., Richman, J. E., Hayes, C. E., & Huestis, M. A. (2016). Drug Recognition Expert (DRE) examination characterisitcs of cannabis impairment. Accident; analysis and prevention, 92, 219-229.

Jones, A. W., Holmgren, A., & Kugelberg, F. C. (2008). Driving under the influence of cannabis: A 10- year study of age and gender differences in the concentrations of tetrahydrocannabinol in blood. Addiction, 103(3), 452-461.

Li, M. C., et al. (2012). Marijuana use and motor vehicle crashes. Epidemiologic Reviews, 34(1), 65-72.

Logan, B. K., Kacinko, S. L., & Beirness, D. J. (2016). An Evaluation of Data from Drivers Arrested for Driving Under the Influence in Relation to Per Se Limits for Cannabis. Washington, DC: AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety.

Northwest High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area. (2016). Washington State Marijuana Impact Report. Seattle, WA: NW-HIDTA.

Ramaekers, J. G. (2018). Driving under the influence of cannabis: an increasing public health concern [viewpoint]. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.1334

Richer, I., & Bergeron, J. (2009). Driving under the influence of cannabis: Links with dangerous driving, psychological predictors, and accident involvement. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 41(2), 299-307.

Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area. (2017). The Legalization of Marijuana in Colorado, The Impact, Volume 5. Denver, CO: RM-HITDA.

Rogeberg, O., & Elvik, R. (2016). The effects of cannabis intoxication on motor vehicle collision revisited and revised. Addiction, 111(8), 1348-1359.

Ronen, A., et al. (2008). Effects of THC on driving performance, physiological state and subjective feelings relative to alcohol. Accident; Analysis and Prevention, 40(3), 926-934.

Ronen, A., et al. (2010). The effect of alcohol, THC and their combination on perceived effects, willingness to drive and performance of driving and non-driving tasks. Accident; Analysis and Prevention, 42(6), 1855-1865

To request materials email the Institute for Behavior and Health at ContactUs@IBHinc.org